RÓISÍN SORAHAN packed her bags, dusted off her ‘Teaching English’ cert and headed to the Far East – and hasn’t looked back since.

WE WERE directed under an ornate red arch which straddled a narrow street that heaved with motor-bikes of all shapes and sizes.

As we wandered the length of the strip, the traders’ faces transformed from dour boredom to full-beam excitement. We weren’t just potential customers; we were the foreigners in town.

Eventually we hovered around one bike long enough to signal the start of negotiations. Our attempts at crash-course Chinese were met by a mixture of emotions. “I’m Irish”, I stumbled in Mandarin. The owner frowned. “I’m an English teacher,” I added. Cue, nodding and laughter. Eventually conversation collapsed into more reliable forms of communication: pointing and gestures.

The bike’s loveliness was paraded in front of us as the owner lovingly ran his hands over its body. After a suitable courting period, a price was suggested. We chortled and named our counter-offer. It was clear that we weren’t just making a deal. We were making a connection, and this could not be rushed.

We were in no hurry. Life as an English teacher in China is not a harried affair. We made small talk, drew a crowd and eventually sealed the deal.

For 3,300CNY (€370) we bought ourselves a 100cc bike and two construction worker hats. It was a steal. And, as the engine size fell outside government regulations, we didn’t need to tax it, insure it, or possess a licence to drive it. Ah, China. I had been here just a week, and already I was smitten.

I hadn’t planned to come to China. I had been a fully functioning member of the Irish workforce for 10 years before I did the unthinkable. In 2008, as Ireland teetered on the edge of economic atrophy, I quit a perfectly good job to squander my fortune and travel the world.

Two years later, curtailed by the necessity of having to stand still long enough to earn more money, I dusted off the Teaching English as a Foreign Language (TEFL) cert I had acquired on a whim back in 1998, and headed to China with my partner, an American IT programmer.

But I was entranced by the idea of travelling in China and considered the opportunity to learn its language and culture an added enticement.

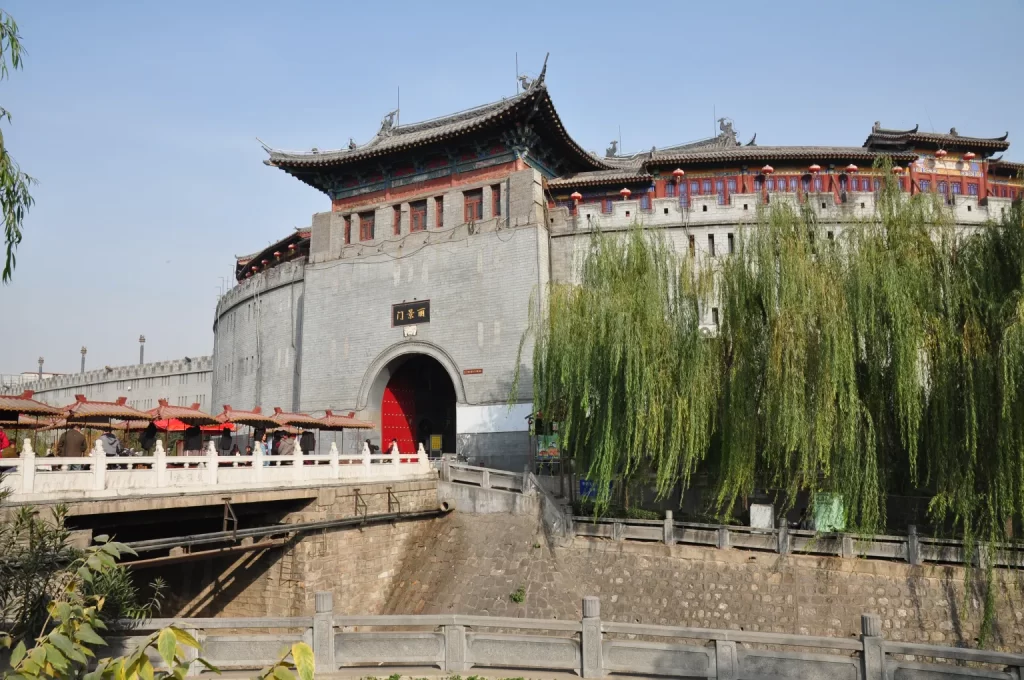

Hénán wasn’t an obvious choice. While it’s home to the Shaolin Temple and four of the eight ancient capitals, its political and cultural influence has long since diminished. It’s considered a backward, rural centre and its contemporary claim to notoriety is that it recently passed the 100 million inhabitant mark, making it China’s most populated region. Where better place, we figured, to peep behind the curtain and see what was really going on?

We arrived in Hénán, the central province, four months ago with contracts to teach English at a private university. I hadn’t set foot in a classroom since my college days and I had never envisaged myself standing at the top of one.

The university that hired us is located on the outskirts of a small town of 800,000 people in this region. A mere hamlet, by Chinese standards, it’s unaccustomed to tourists and its primary contact with Westerners is through its tiny community of foreign teachers.

Most people we meet make the default assumption that every Westerner is American and mere mention of Ireland can be cause for head-scratching. Though one 10-year-old recently leaned across the table, “Can I tell you a sad story?” he asked. I nodded. “Ireland is in big trouble.”

All the students and most of the employees live on the university’s campus. There’s no drinking and no smoking in the college. No religion and no politics in the class-room. There’s no Facebook and there’s no nonsense.

The students are drilled with a strong work and reward ethos, most pronounced in the children of farmers who have scraped together their life’s savings to send their off-spring to college. “Having fun would be a waste of time,” one student assures me.

They also have a strongly cultivated sense of national pride. Both the students and college authorities are anxious that our experience of China is positive. We are given every assistance and great latitude. Our two-bed apartment is palatial in comparison with those of our Chinese colleagues and we’ve just 18 teaching hours per week.

This ethos is mirrored outside the compound walls. People’s overwhelming curiosity about us is tempered by a sense of responsibility towards us. We are constantly stared at and wondered about. However, stand still for a moment and someone will step up to welcome us to China. And if assistance can be given, it is willingly offered.

Without the key to the language and the culture of China, there’s no way to navigate the country without the kindness of strangers. It’s humbling, it’s exciting but, for many, the culture shock can be unnerving. One English teacher wearily explained: “As a foreigner you’re always stared at. You can never blend in. You can’t have a quiet meal anywhere. People always come up and talk to you.”

What’s more, the simplest tasks can become mammoth undertakings. My first attempt to buy train tickets was demoralising. I was faced with an empress doling tickets like favours. She pointed to the time schedule. I couldn’t crack the code. She rattled off something. I couldn’t catch a word. She started to shout at me, though hearing wasn’t my issue. The queue jostled and the guillotine fell. With a wave of her hand, I was dismissed.

It’s confusing, certainly, but it’s the differences that make living in China so interesting. While guilty Western pleasures are abundant in big cities, in small towns they’re in short supply. I’m daily wooed by foods I’m sampling for the first time. Some, granted, are an acquired taste, but I can now brandish chopsticks, spear dumplings and slurp a bowl of 4CNY (€0.5) noodles like a local.

Food is washed down with tea or Báijiu — a gut-warming, 60% steel-proof liquor. Báijiu is the centre-piece of every party and the lead singer at KTV karaoke clubs.

It’s a necessary blow-out to the sobriety of daily life. China means business, literally. Cranes dot the sky-line and buildings are flung up with astonishing speed.

Everywhere I look, people are moving out of their rut. The middle-classes are expanding and black sedan cars speeding towards the province capital have become the new symbols of an aspiring nation. Without the language, I can still read the signals. China is on the cusp of another beginning.

These are thrilling times for the People’s Republic. It’s a country on the brink of economic stardom and it’s anxious to prepare the new generation for its role in the world market-place.

With 25 million university students clamouring to learn, this English teacher and traveller is being offered front-row seats to the show.

© Róisín Sorahan

Article originally published by Irish Independent