In Conversation – Joystory Interview

22 Feb. 2022

Joystory.blogspot.com

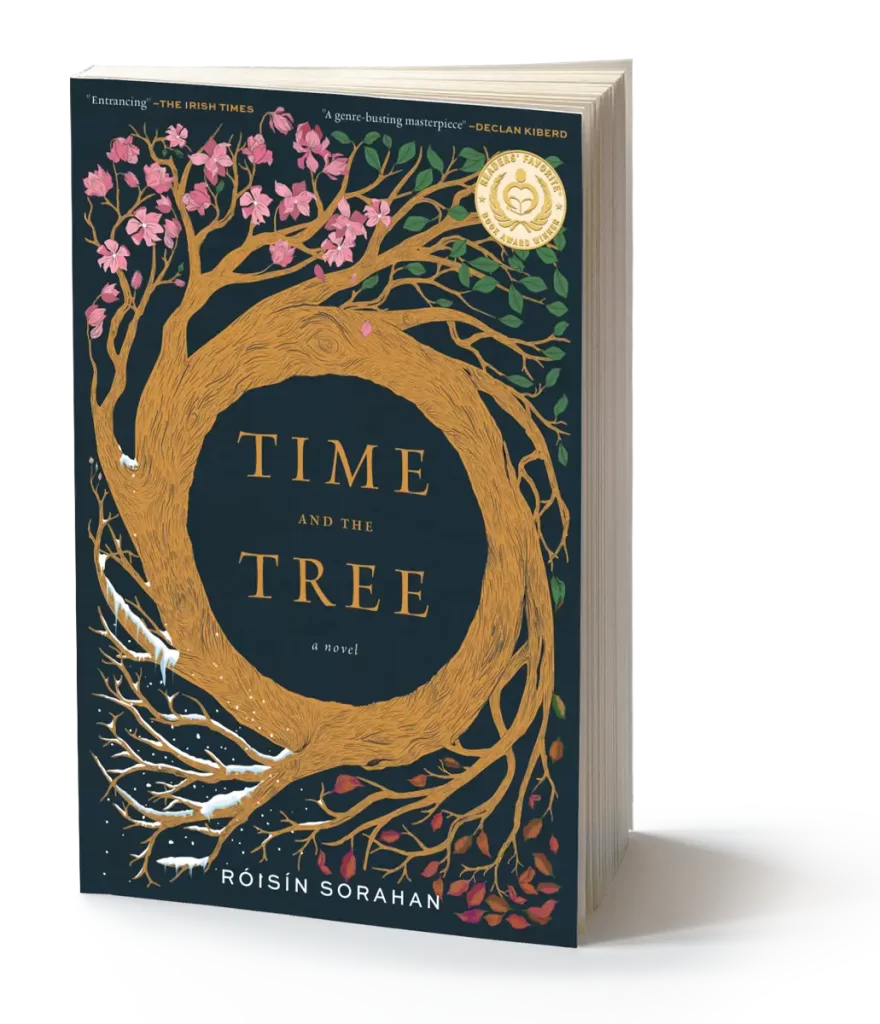

RÓISÍN: It means a lot to me that you enjoyed Time and the Tree. Thank you for taking the time to read it, Joy. I also appreciate such thoughtful and insightful questions.

I believe the reader completes the creative process. They bring their memories, experiences, failures and aspirations, and sculpt their own meaning from it. It is with this in mind that I approach your questions. I don’t want to influence, or shape, the response to Time and the Tree. It’s important that the reader creates it in their own image, according to their need and belief, every single time.

But, to answer your first question, my name, Róisín, is Irish. Phonetically it is pronounced: Row-sheen.

JOY: I hope that this first set of questions related to Influences is enough different from the question ‘Where do you get your ideas?’ that you won’t, as most authors do for that version, turn from them in disgust and horror.

RÓISÍN: Authors are often the worst people to describe their work. Articulate on the page, we stutter over words to encapsulate it. Some have been known to bark. I recall Samuel Beckett’s response when prodded: “No symbols where none intended.”

But, I shall try…

JOY: What and where were the landscapes you encountered from earliest memory to the last sentence written that influenced your development of your story’s landscape?

RÓISÍN: I grew up in Dublin, in Ireland. It’s a fantastic city. One of my favourite aspects of it, however, is how easy it is to get out of it and find oneself in the hills, smothered by gorse, or on the coast, doused by the smell of the sea.

Some of my earliest, and happiest, memories, are of sojourns along the west coast of Ireland. There’s magic there, it its unruly wildness.

My parents were attuned to the rhythm of the seasons. My mum grew things. My dad took enormous pleasure in the rise and fall of a wild creature’s chest. I learned to observe, and respect, the natural world, from them.

In my childhood, and in all that followed, mountains existed to be climbed; and admired. And trees, well, they offer enormous comfort, don’t they? Perhaps it’s their heartbeats that resonate with us, on a visceral level.

Our small garden, growing up, was also a place of wonder. I recall hunkering down, head bent over the first flowers of spring. They never failed to draw me closer, and astonish me, every single time. I could have spent hours looking at them. I possibly did.

As an adult, I took to the road, lured by the siren’s call. I’ve traveled across so many borders, now, that boundaries mean little to me. The world is astonishing in its beauty, and in its capacity to surprise. So, too, are the people one meets.

I drew on my travels when recounting the Wanderer’s experiences. The road itself became an important landscape in my tale, with all its promise, and uncertainty.

JOY: In this vein I can’t help but wonder if you ever wandered alone in a forest as a child as Boy does?

RÓISÍN: I wandered, certainly. But with the knowledge that my parents were close by, so I never felt lost. Perhaps this sense of security is reflected in the Boy’s ease in this environment.

But, you are right to identify the important role the forest plays in the story.

It links into the tradition of the fairy tale, where the forest is an enclosed world that can represent both danger and refuge. It thrums with possibility and life. And, for all that it keeps its secrets in the open, it hints at another space, that cannot be seen, that hovers on the edge of awareness.

The forest is both a portal, and a boundary.

JOY: From earliest memories to the last sentence written, what were the cultural experiences from your life that influenced the development of Time and the Tree?

RÓISÍN: I live my life deliberately. I take risks and make choices. And I take responsibility for these choices. Even the bad ones.

It’s a decision to live in this manner. It opens one to possibility; and it comforts with the knowledge that nothing is immutable, and change is always within reach. I remind myself that all that is past has significance, in bringing me to where I am. And all that follows flows from this moment.

It makes me aware of time. It also helps me to understand that my relationship with time is within my control, and a decision that I make.

This is one of the central tenets of Time and the Tree. It challenges the reader to reflect on choices they have made, from a fresh perspective. It also offers hope.

As our capacity for tyranny and self-destruction is enormous, so too is our light, and our ability to change.

I am also a proponent of the Philosophy of Happiness. This, for some, is a tricky one. Culturally, we are encouraged to think of others, and do the right thing. This is critical for operating within social structures. However, this message has been packaged in guilt, and wrapped in self-sacrifice. Dousing the light, to let others shine.

This, of course, is antithetical.

Women, I believe, suffer particularly from societal pressure to deny personal need, desire and ambition, for the good of the tribe. They are defined by their roles. And celebrated, or shamed, accordingly. Little wonder that ‘the invisible woman’ haunts galleries, history books and tales of derring do.

This diminishes all of us. In supressing the will to love and learn and be, it scrubs words and drags darkness into the space where the light should be. Without happiness we cannot help ourselves, let alone another.

The pursuit of happiness is explored in Time and the Tree. It examines the importance of self-actualization. It also illustrates the cost of erasing the self; underscoring the fundamental tenet that underlies pretty much every spiritual philosophy: love yourself; love others.

JOY: Here I can’t help but wonder if you discovered and loved allegory type stories as a child and, if so, which ones?

RÓISÍN: I devoured fairy tales, and all stories magical: The Brothers Grimm; Enid Blyton; Hans Christian Andersen. Then I moved on to fantasy. I read The Lord of the Rings numerous times.

I just finished Kelly Barnhill’s The Girl Who Drank the Moon, which utterly bewitched me.

Children’s literature continues to fascinate me. It’s subversive. Magic is another word for possibility. And the format of the fable is extremely powerful.

I used it in Time and the Tree because it employs a childlike simplicity that takes you by the hand and brings you to places you might never have otherwise ventured. Before you know it, you’re in the basement in the dead of night, while the wind howls and the electricity fails.

Typically, fables also lead you home again; though the meaning of ‘home’ may have dramatically changed from when you set out on the journey.

JOY: From earliest memories to the last sentence written, what aspects of your personal history influenced Time and the Tree?

RÓISÍN: I quit a good job to travel the world in pursuit of happiness. When I set out, I figured I’d find places that lured me into staying. However, I discovered that I was never happier than when my nose was pressed against the window of a filthy bus. The road became my destination, and I had time to think.

The opportunity to allow the mind to meander is a novelty in modern times. When my brain quit making lists, it had space for ideas.

I slept in countless beds, packed and re-packed my belongings, shedding stuff, where I could. My sense of need, my understanding of my blessings and opportunities, and my concept of home, evolved.

During this time, I met numerous people who influenced my thinking and guided me towards my path. The opportunity to learn and practice Vipassana mediation in retreats in Dehradun in Indian, and in Shelbourne, Massachusetts, in the US, played an important role in the evolution of Time and the Tree.

JOY: Here I’m especially interested in how your personal encounters with loss and grief played a role in developing the core philosophy of Tree revealed near the end. But if there are any others that come to mind I welcome them as well.

RÓISÍN: Death and life are intertwined. Endings and beginnings. Complicated stuff.

We reach a point in our lives, where we all experience it, at some stage. There is no avoiding it.

Grief and death are not to be confused, however. Grief is painful and ragged. The cost of loving deeply.

Death is what gives meaning to life. Without winter, there would never be spring.

JOY: Why did you choose to keep the Boy nameless and untethered to any hint of a life outside the forest? No parents, siblings, culture of his own? No past before the Tree?

RÓISÍN: The Boy is an archetype. He features powerfully in the story, but his role is to question, to seek, to be the site over which a battle is raged. And it is his function to transition from innocence to knowledge.

He is a critical catalyst in the tale. But, most importantly, in retaining him featureless, he is a vessel into which the reader can pour themselves.

JOY: As I read your description of Weaver’s Web in the far North I got chilling associations in my mind with our World Wide Web. Was this intentional? Part of your vision? Or just a matter of your Story acting like a Rorschach’s inkblot for individual readers as so many do?

RÓISÍN: Tyranny exists in many forms. We have witnessed this throughout history, and our current time is no different. The mechanisms of power change, but the intentions do not.

When I wrote the North, I had ample references. All of our time. They coalesced to shape this dystopian realm. The political unrest we’ve seen these past few years, and the misinformation that foments fear and creates the Other, all played into the evolution of the Weaver’s web.

JOY: At one point I saw such a strong correlation between the relationship of Time and his Shadow to our Patriarchal culture’s marriage dynamic that I half expected you to reveal them as the Boy’s parents. Rorschach or real? Have you encountered in reading or travels any other culture types that use time tyranny the way Patriarchy does? Or any Patriarchy that did not? Or any at all that eschew time tyranny and yet exhibit sustainable success?

RÓISÍN: That’s a wonderful way to read the story, Joy. And I think the relationship between Time and the Shadow can be understood in many different ways.

More generally, time has always held great sway, in one way, or another. The pressure to get the hay in before the rain falls; the need to get the animals into the barn, before the night comes. The roll of the seasons, and the pendulum of day and night, have always been batons that beat out the measure of days and lives.

Then, the industrial revolution monetized time. And, in placing a value on time, it handed it to those with earning potential. Traditionally, men. The breadwinners sloughed to the factories and counted their days in hours spent earning a crust. It wasn’t great. But it was better than time being counted for nothing, which was the case of the domestic, female, sphere. Linking time to money created yet another power imbalance in the Patriarchal structure.

However, there are other ways to engage with time. And this is what Time and the Tree explores. Time is a construct of our making. The role it plays in our lives is ours to choose. It can be the yoke to which we tether our lives, as we strain and yearn towards a better future; or it can add weight to the present moment, with the knowledge that it too will pass, regardless of its wonder, or its pain.

This is central to Buddhist thinking, and it is an ethos that is slowly seeping into Western culture.

JOY: Why does Tree welcome Time and Weaver and exhibit a faith and hope that they can be redeemed? Are there some aspects of these two characters that are essential to life if their attributes and actions had not been corrupted? As distasteful as I found them I also registered empathy for them and this resonates with the personal philosophy I developed after I broke with the fundie cult I was raised in: That there is no such thing as an irredeemable sentient being. Can you riff on this concept?

RÓISÍN: I don’t believe in the lost cause. Any more than I believe in our power to change another. We can help. We can support. And we can guide. But the impetus for change lies within the individual.

Our personal capacity for destruction and self-loathing is matched by our ability to evolve. It is within our power to create new thought patterns and relationship habits. We can change how we engage with the world, even when we cannot control society’s mechanisms. Who we spend time with; how we listen; the words we choose to speak; the silences and counsels that we keep. We can put out a hand to help another. Equally, we can decide that we ourselves are worth saving.

If this pandemic has reminded us of anything, it is that humans are adept at evolving and surviving. Regardless of how much we fight it, and how much it frightens us, change is always within our grasp.

The Tree does not bar the path to any who seeks its counsel. It does not stand on judgement. Nor does it crush its limbs, by flinging itself against the world. It helps the reader understand that “Time gives meaning to endings and beginnings and encourages us to dive into the chasm that lies between.”

It also throws the gauntlet to the reader to reflect on their path and the choices they’ve made, and the role they have cast Time in their lives.

The Weaver is more difficult to empathise with. Yet, the Tree consistently approaches her with compassion, even as it displays its steels. The Tree will not compromise, for all the Weaver’s wheedling. It will not be less than what it is.

© Róisín Sorahan